Composition in the 21st Century

Some Thoughts on the Topic of Musical Time

Dr Ian Percy

Senior Fellow Higher Education Academy

Introduction – The Reception of Linear Motion:

Composition is the corporealisation of incorporeal sound1.” To be more specific, composition is the corporealisation of incorporeal sound through concept, architecture and creative realisation, framing a work between near silences, within a finite linear space, with sympathy for pacing, proportion, purpose and aesthetic.

Composers take an invisible acoustic phenomenon and through a combination of design, process, theory and instinct determine its shape, duration, texture and intensity interwoven with an emotional message and/or intellectual methodology. Analysts, theorists and musicologists then discuss its structural components (including ambiguous elements of musical character and personality), interpreting these characteristics and analogies in detailed retrospect, whilst engaging with countless methods and an extensive vocabulary through which to describe and illustrate the goal-oriented focus of the piece (stasis, progression, momentum, crescendo, tension and release).

Western art music is often obsessed with goal-oriented momentum, but the concept of travelling towards a goal must always exist even in the most abstract of music, even if that goal is simply to end. To have a goal means that the work must always be received in real-time, for a future goal implies a linear perception. Therefore, the literal reception of music is always linear.

For the composer, time is not linear (not until performance). Composers can rearrange and manipulate time, slow it down and speed it up. One can even freeze time (vertical time)2.

1 Corporeal: 1. Having, consisting of or relating to a physical material body; not spiritual 2. Not immaterial or intangible; substantial (of substance). Incorporeal: Having no physical (material) body or form, of the spirit.

2 Kramer, Jonathan: The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies, New York, Schirmer 1988.

Time

1. Time is a continuum in which events succeed each other.

2. Time is a measurable period during which an action, process or condition exists or continues.

3. Time is a continuum of experience in which events pass from the future through the present to the past.

Time is a linear continuity through which we all travel, living in the present, reflecting upon the past and looking towards the future. Chronometric time is equidistant, linear and constant (though can be affected by distance and meteorology). Humans also experience time as a constant: a linear continuum from the past, through the present and into the future, but our perception of the passing of time varies for many reasons.

Human Perception/Reception:

1. Psychological: Of the mind, will, morale.

2. Physiological: Characteristic appropriate to normal healthy function.

3. Intellectual: Knowledge and prior understanding.

4. Emotional: Intervals, cadences: Why do we FEEL what we hear? Folk songs.

5. Spiritual: A room full of voices, a lyrical string quartet: Sacred Music.

6. Metaphysical: Existing beyond nature – supernatural.

Our senses experience music through complex interacting levels of reception, perception, mood, instinct and emotion. Time remains a linear continuum, but the rate of passing time becomes proportionate within the musical journey. The rate of ‘musical time’ (tempo and intensity) can also alter quite dramatically and we are removed from the boundaries of the equidistant chronometric.

Can musical texture, intensity and activity affect the way we experience linear time? Does time travel faster when we are listening to energetic music with loud dynamics and gathering rhythmic momentum? When listening to an isometric isorhythmic piece locked within a static or slow-motion modality, does time slow down? Then there is the added consideration of time being relative to the amount of enjoyment we are getting from the experience, how familiar we are with the piece and therefore how long we expect it to last: The perception of musical time is a proportionate variable.

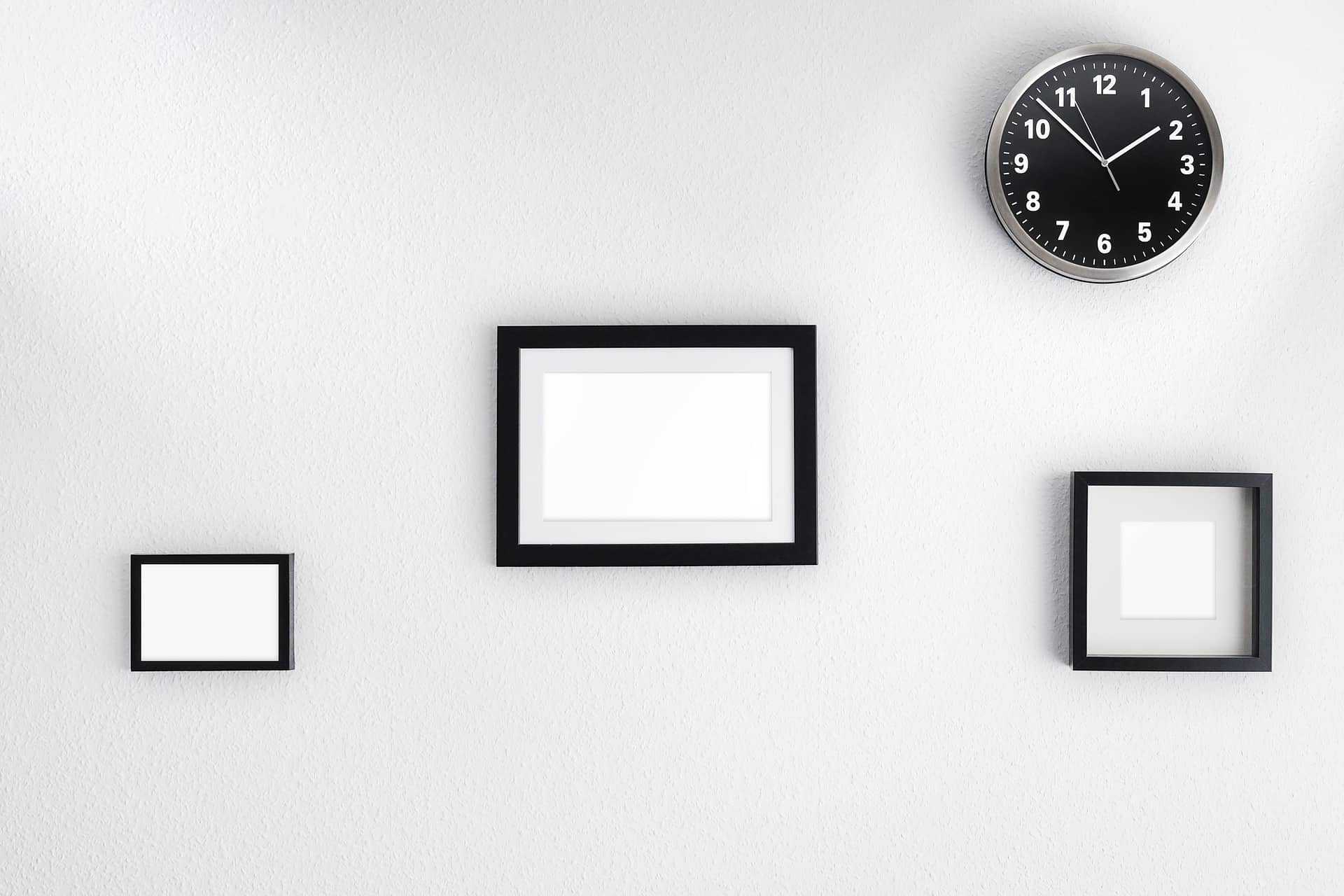

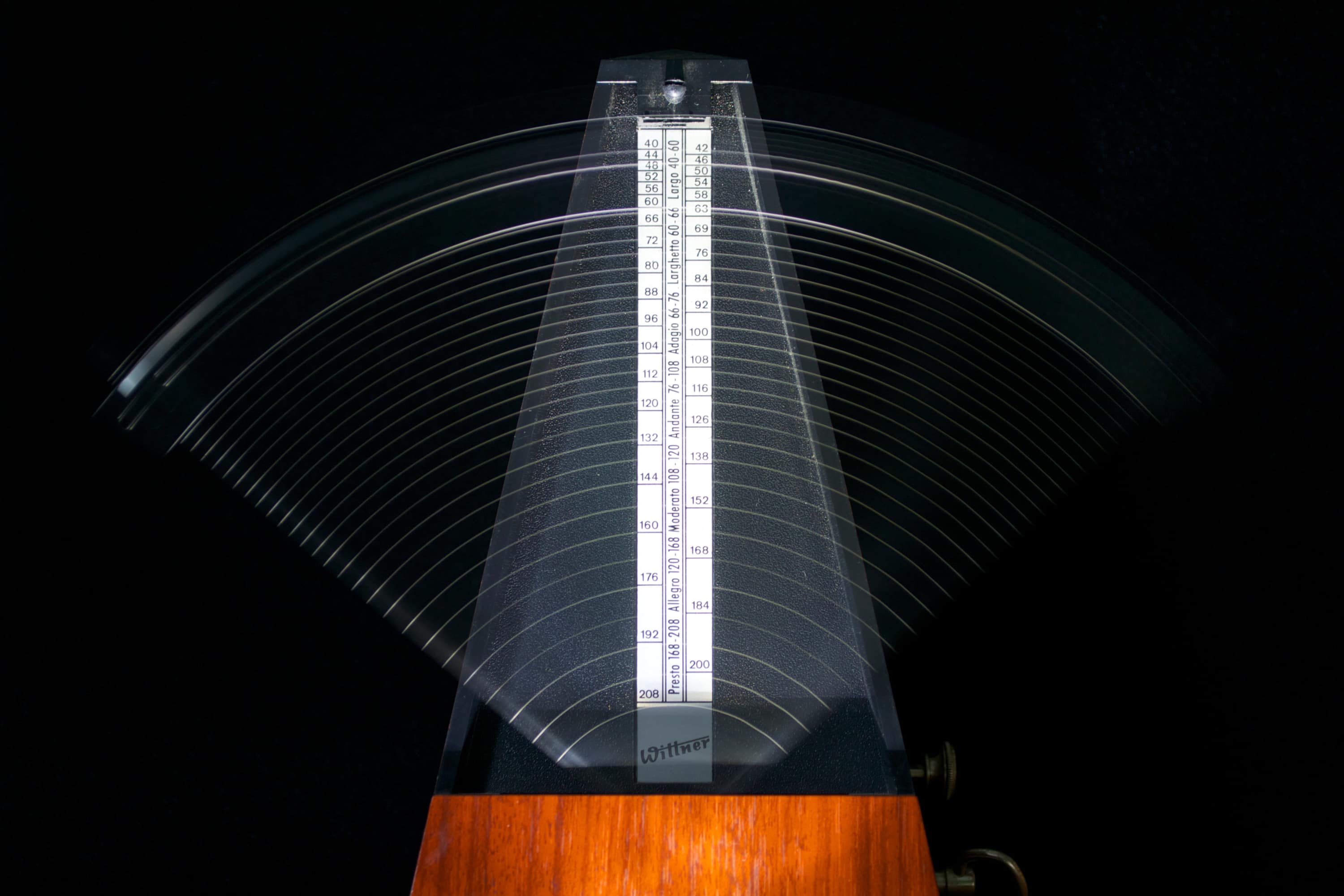

Tempo:

Tempo indicates the rate of pulse, the speed of the music, but taken literally, tempo means the speed of time3. If we therefore slow down the pulse will this slow down the perception of passing time?

During performance of the completed score one expects the conductor to stretch and shrink ‘musical time’ as they feel fits the context of the music. The musicians and the ambience of the venue ultimately decide the tempi in smaller ensembles.

Does the piece last longer if the tempo is slower? Of course it lasts longer measured in chronometric time, but perhaps we still receive and perceive the same sonic journey? If so, then the passing of time was relative during the listening experience, not equidistant.

Elgar (Edward, 1857-1934) can be an important case study in this regard. Elgar’s interest in documenting and disseminating his music through emerging technologies in the early twentieth century leaves us with a portfolio of work conducted by the composer.4 There are radical changes in tempo between the score and the recordings, and also between different recordings of the same piece, but we generally experience the music as a recognisable reoccurrence of the same sonic journey.5

3 Tempo from the Latin Tempus (time) (tempus fugit – time flies).

4 Elgar conducts Elgar - The Complete (Acoustic) Recordings 1914-25. Music & Arts, USA, 1911

5 The Complete Electrical Recordings of Sir Edward Elgar: Recorded at the Kingsway Hall, London, 23rd March and 13th June 1928. Beatrice Harrison (cello). New Symphony Orchestra conducted by Elgar: EMI Classics, 1993.

Pulse: Proportional Tempi and Metric Modulation:

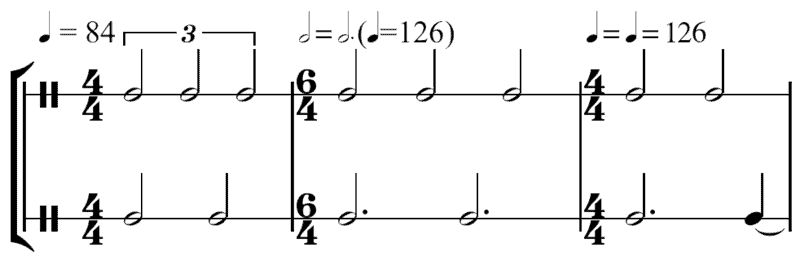

Pulse is a primary factor in the perception of ‘musical time’, but this can be manipulated and confused (purposely blurred) by the composer through elements of metric modulation (or tempo modulation) where pulse and time do not equate to the same thing.6

“There are four different types of metric modulation: Pulse Modulation, Duration Modulation, Abrupt Modulation and Written Accelerando Modulation serving four different functions: Formal Division, Transition, Time Control, and Character Designation.”7

Metric modulation and pulse methodology shows how ‘musical time’ and its linear perception is actually a comparative illusion, a form of temporal solfège relative to the many variables of individual reception.

6 Metric modulation is a term introduced by Richard F. Goldman (The Music of Elliott Carter, Musical Quarterly 63, no.2 April 1957) to describe certain passages in Carter’s Cello Sonata (1948), the label is now applied to any work engaging with proportional pulse methodology.

7 Jason Hobart: Classifications and Designations of Metric Modulations in the Music of Elliott Carter, Music Theory Midwest, 2011

Form:

Form can be abstract, geometric, proportionate, symmetric and/or asymmetric, but is an important element in the perception of ‘musical time’ and a primary consideration for the composer within the corporeal score. Musical character influences chronological placement, but form is flexible during composition, it can be rearranged, displaced, stretched and shrunk: i.e. Birtwistle’s ‘blocks’ (Silbury Air, 1977) and Lutosławski’s ‘mobiles’ (String Quartet, 1964).

Both of these compositional forms are very similar in concept, they both explore self- contained material which can be rearranged or displaced during composition. However, Birtwistle refers to the process as static (interrupting the flow of linear time) and Lutosławski refers to the process as fluid (connecting the flow of linear time).

“I have often alluded to my music of landscape presenting musical ideas through the juxtaposition and repetition of ‘static blocks’ or, preferable for my terminology, objects. These objects themselves being subjected to a vigorous invented logic via modes of juxtaposition, modes of repetition, modes of change. The sum total of these processes being a compound artificial landscape of ‘imaginary landscape’, to use Paul Klee’s title. The Pulse Labyrinth shown at the start of the score is not intended as a conducting aid. Rather, it gives an indication of the compositional logic behind the interrelationships of tempi used in this piece. This is based on a process of continuous metric modulation.”Sir Harrison Birtwistle 8

“The term ‘mobile’ refers to the variable length of sections in different instrumental parts, which is connected with the group playing ad libitum. The work contains a number of very long sections, lasting several minutes each, which leads to great differences between individual performances. That is why I coined a phrase which suggests the mobility of various layers within the work, depending on the way they are performed. I would like to stress that I was not aiming specifically at this variability within the long sections. I wanted merely to loosen the time connections and to achieve a specific texture, which we might call a ‘fluid’ texture. This kind of composition could be compared, paradoxically, with sculpting in non-solid, almost liquid material.”Witold Lutosławski 9

It is interesting to note how both of these composers studied the work of visual artists (Lutosławski/Calder10 and Birtwistle/Klee11) to inform their sense of musical structure, function and proportion; using visual references to help establish a corporeal form within this non-corporeal acoustic art.

8 Harrison Birtwistle. Silbury Air for chamber ensemble Study Score (1977, rev. 2003). Universal Edition, London, 1979

9 Witold Lutosławski. String Quartet Study Score (1964). Excerpts from letters to Mr. Walter Levin, first violinist of the LaSalle Quartet. Edition Wilhelm Hansen, London, 1968

10 Alexander Calder (1898-1976): American sculptor best known as the inventor of the mobile, a type of structure/ sculpture which can be mechanised or made with lightweight materials in order for components to move in response to the motion of the air around it.

11 Paul Klee (1879-1940): Swiss [considered German-Swiss]. Author of Pedagogical Sketchbook. Praeger, New York, 1972 (originally published 1953)

Conclusion:

In conclusion, time is a linear continuity through which we all travel, living in the present, reflecting upon the past and looking towards the future, but due to the many variables within the human perception of passing time and the way composers can manipulate the rate (or perceived rate) of ‘musical time’, it seems musical form is not bound to temporal linearity. Chronometric time remains constant and the literal reception of music IS linear, but composers in the 21st century are temporal alchemists escaping the mensural tyranny of a 1000-year-old system of notation.

Tempo, pulse, meter, bars, beats, dynamics, texture, intensity, motion, activity and goal all serve as suitable topics for analysis and musicological discourse, but don’t always equate to proportional symmetry within the corporeal score or accurately reflect the incorporeal listening experience. All levels of human perception and their many combinations affect the passing of time. Therefore, we must move past the notion of chronometric and mensural time and generally reevaluate how we consider, measure and discuss the vertical and linear motion of ‘musical time’.

Dr. Ian Percy (2022)